Look, there are a lot of comics out there. Too many. We can never hope to have in-depth conversations about all of them. But, we sure can round up some of the more noteworthy titles we didn’t get around to from the week. Today, we discuss Groot 5, Plutona 2, Miracle Man 3, The Surface 4, and We Stand On Guard 4.

Groot 5

Drew: How do you show true loyalty in a comic — that is, what does it look like? Is it following a friend across the universe? Is it suffering in silence just so you can be around them? Is it dying so that they may live? In just a few issues, Groot has managed to cover all of those bases, but writer Jeff Loveness manages to find a new depth to show just how much Groot cares about Rocket.

Drew: How do you show true loyalty in a comic — that is, what does it look like? Is it following a friend across the universe? Is it suffering in silence just so you can be around them? Is it dying so that they may live? In just a few issues, Groot has managed to cover all of those bases, but writer Jeff Loveness manages to find a new depth to show just how much Groot cares about Rocket.

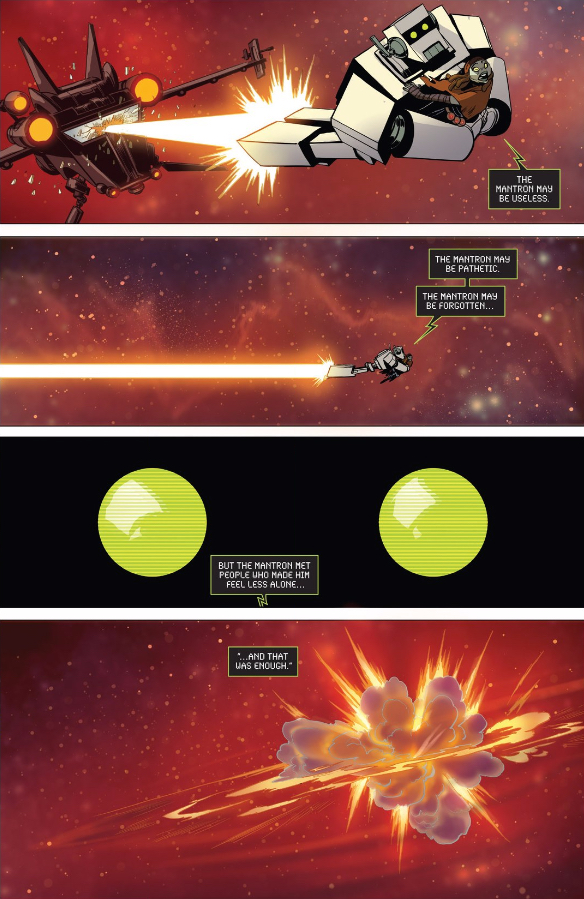

Much of that comes in the shape of an arduous battle with Eris’s goons, but the thing that really caught my attention here is how Rocket and Groot’s friendship is reflected in the crack team Groot assembled to rescue Rocket in the first place. None seemed more moved by their friendship than Mantron, who counts the motley crew here as his only friends. That seems like a cute detail (which turns into an even cuter plot point) until Mantron up and makes the ultimate sacrifice. Stepping in to be blown to smithereens is well-worn ground for Groot fans (heck, Loveness pulled a similar trick in last month’s issue), but Loveness manages to give Mantron’s final moments some real poignancy.

In true Groot fashion, a shred of Mantron survives, meaning that he’s not really dead, but it was touching all the same.

Plutona 2

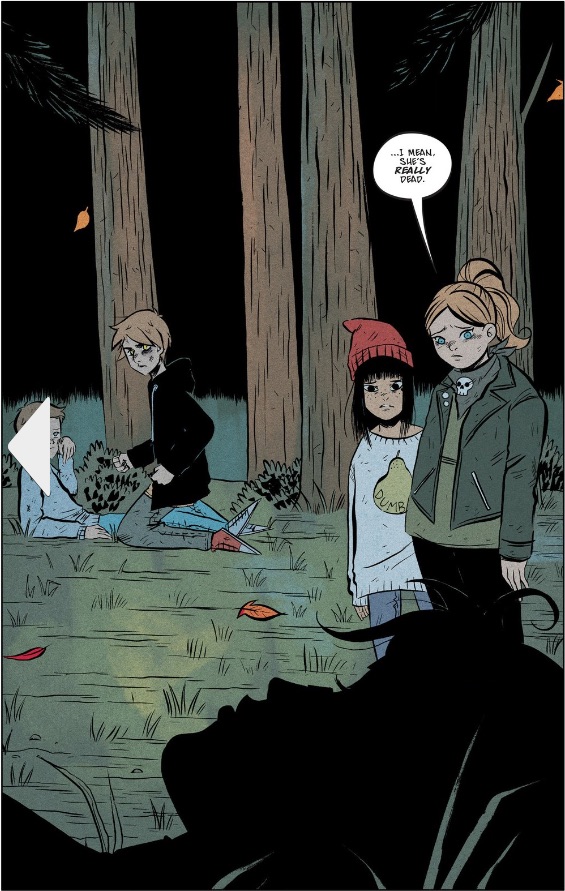

Ryan M.: Plutona 2 starts right where the first issue left off. The body of a Superhero and the five children who found it in the woods. The body is featured on nearly every page. She lays in the foreground of the action, moving in and out of silhouette. Her image adds weight to all of the action happening beyond her. The bulk of the issue is simply a discussion among the kids, but thanks to the layers of characterization and world-building, it remains compelling. Jeff Lemire and Emi Lenox’s dialogue reminds me of a John Hughes movie. There is empathy in the writing, even if the characters can’t offer it to each other. Except for Mike, these kids are ready to play act as adults, even if what they’re facing is too much for them. Look at their expression in the following panel as they regard the body. They all look so young and wide-eyed. Even Diane’s shoulder spikes are absent in the image, stripping away her DIY veneer of toughness.

Ryan M.: Plutona 2 starts right where the first issue left off. The body of a Superhero and the five children who found it in the woods. The body is featured on nearly every page. She lays in the foreground of the action, moving in and out of silhouette. Her image adds weight to all of the action happening beyond her. The bulk of the issue is simply a discussion among the kids, but thanks to the layers of characterization and world-building, it remains compelling. Jeff Lemire and Emi Lenox’s dialogue reminds me of a John Hughes movie. There is empathy in the writing, even if the characters can’t offer it to each other. Except for Mike, these kids are ready to play act as adults, even if what they’re facing is too much for them. Look at their expression in the following panel as they regard the body. They all look so young and wide-eyed. Even Diane’s shoulder spikes are absent in the image, stripping away her DIY veneer of toughness.

Miracleman 3

Patrick: Art, by its very nature is obsessive. The artist selects a subjects and then explores it from so many angles — literal and figurative — that they can then express it back in way that feels honest or relevant. In their third issue of Miracleman, Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham turn their focus to another artists’ expression of a subject. That, of course, is an expression that they’re inventing wholesale, and the whole thing ends up being a dizzying exercise in borrowed perceptions and the ego that comes from making great art.

Patrick: Art, by its very nature is obsessive. The artist selects a subjects and then explores it from so many angles — literal and figurative — that they can then express it back in way that feels honest or relevant. In their third issue of Miracleman, Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham turn their focus to another artists’ expression of a subject. That, of course, is an expression that they’re inventing wholesale, and the whole thing ends up being a dizzying exercise in borrowed perceptions and the ego that comes from making great art.

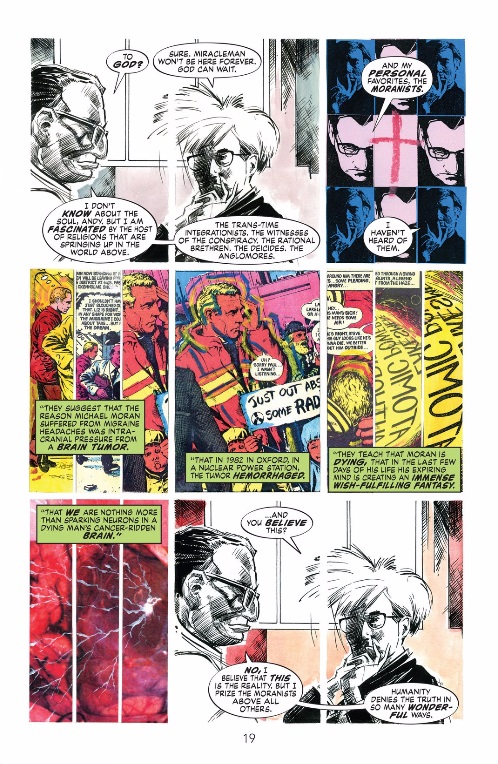

That’s kind of a heady thesis statement. And it may technically be two separate thesis statements that I jammed into one sentence, but this is a dense fucking issue. The issue opens on the resurrection of Dr. Emil Gargunza, a classic Miracleman villain, in the bowels of the Miracleman pyramid in London. He’s a robot body infused with the holographic memories of is life battling the aforementioned hero. But rather than view this iconic villain through a neutral lens, Gaiman and Buckingham invoke pop artist icon Andy Warhol. Actually, there are 16 Andy Warhols (Andies Warhol?), all robot copies in the same vein as the Emil robot. This means that everything gets filtered through a sensibility that is instantly recognizable, as Buckingham does his best Warholian flat drawings and photo-collages. The conversations that this fictional villain and real-life artist have are mindbendingly self-referential, and the artwork does its best to match this furiously meta pace. Buckingham seldom deviates from a 2×3 or 3×3 grid in his panel layouts, except when really tapping into Warhol’s aesthetic. At that point, every panel has the ability to become an entire page unto itself, with it’s own internal 3×3 grid.

It’s the closest this series comes to acknowledging that it’s less about the characters of the Miracleman family, and more about how the artists view those characters. Gaiman and Buckingham are pop artist icons in their own right — though, maybe it’s a touch egotistical to make their avatars 16 Andy Warhols — and this issue seems like an admission that they best they can ever hope to do is illustrate how tricky it is to explore these subjects without exploring themselves.

The Surface 4

…the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author.

Roland Barthes, The Death of the Author

Drew: Comics have long had a formalist bent. Whether that’s a historical coincidence or a reflection of their inherent nature is a question worth pursuing, but the point is: we tend to think about comics in terms of audience participation. Scott McCloud called it “closure” — that the creation of a world between panels happens entirely within our heads. We’ve long reflected that attitude here, focusing much more on our own experiences of comics than fretting over whatever intentions we might imagine for the author. But then there are comics like The Surface, which simply comes out and says what the author is thinking.

Drew: Comics have long had a formalist bent. Whether that’s a historical coincidence or a reflection of their inherent nature is a question worth pursuing, but the point is: we tend to think about comics in terms of audience participation. Scott McCloud called it “closure” — that the creation of a world between panels happens entirely within our heads. We’ve long reflected that attitude here, focusing much more on our own experiences of comics than fretting over whatever intentions we might imagine for the author. But then there are comics like The Surface, which simply comes out and says what the author is thinking.

This isn’t the first time writer Ales Kot has stymied my formalist approach to comics (and I hope it won’t be the last), but this is by far the most pointed. Much of this issue finds Ales Kot (or at least a semi-non-fictional Ales Kot) addressing the reader directly, acknowledging what parts of the story are fiction, and giving us details on when and why they were conceived. It’s a penetratingly open approach from a writer who has heretofore presented rather impenetrable works, which makes me question the apparent transparency of this issue. Could the guy who soaked his Secret Avengers run in Borges allusions really write a story where a dying father represents a dying father?

I have no idea, but that’s precisely what makes this issue so fascinating. Folks looking for a linear conclusion to the stories of any of the characters introduced in issue 1 are sure to be disappointed, but for me, learning that all of these characters are (maybe) manifestations of Kot’s emotional scars is more than satisfying enough. He’s working shit out right on the page — facilitated by a particularly game Langdon Foss — but that also means he’s providing a front-row seat into his process. That may be kind of disgustingly voyeuristic, but we’ve already agreed that this story is more about the Author than the audience, right?

We Stand On Guard 4

Taylor: Issue 4 of the series detailing the future war between America and Canada continues with the fallout from the American’s discovering the secret hide-out of the our Canadian freedom fighters. Before all hell breaks lose in an underground battle involving robotic dogs and gorillas, flying drones, and collapsing cave systems, Highway and Qabanni have an argument about who gets to drive the captured American Mech they possess. Highway argues he should, being that he is a descendant of Native Peoples. Qabanni believes she should drive it and gives the following reason for her argument.

Taylor: Issue 4 of the series detailing the future war between America and Canada continues with the fallout from the American’s discovering the secret hide-out of the our Canadian freedom fighters. Before all hell breaks lose in an underground battle involving robotic dogs and gorillas, flying drones, and collapsing cave systems, Highway and Qabanni have an argument about who gets to drive the captured American Mech they possess. Highway argues he should, being that he is a descendant of Native Peoples. Qabanni believes she should drive it and gives the following reason for her argument.

In a nutshell, Qabanni loves Canada because they accepted more Syrian refugees than the United States. While that’s fair in and of itself, a problem with it is that it’s not true. The US and Canada have to date both committed to taking 10,000 refugees from Syria. So, unless writer Brian K. Vaughn is hinting at a past or future that hasn’t happened yet, this is a false statement. While I realize We Stand on Guard is a work a fiction, it’s presented as being a possible future of our current world. As such, the title behooves itself to have accurate information when referencing events from our current time. Facts that don’t check out make this already far-fetched series all the more difficult to read.

This speaks to a larger I have with this series. Throughout this issue the Americans are presented as being cruel, manipulative, and basically evil. They murder people, double-cross, and are ruthless. The Canadians meanwhile are portrayed as being persecuted saints fighting for a righteous cause. What this does is make it seem like there is ever such thing as a righteous war. True, maybe one side is more in the right than the other, but to paint every member of a particular side as either being good or evil veers this series into the realm of propaganda. It’s not that I’m patriotic and hate to see my countrymen portrayed negatively. Rather, I just believe that in war it’s never a case of good versus evil.

The conversation doesn’t stop there, because you certainly read something that we didn’t. What do you wanna talk about from this week?

1) Groot was cool. I think I’m glad it was a miniseries. I liked it, but five issues was enough. They could make a good hour long cartoon off this story.

2) “Rather, I just believe that in war it’s never a case of good versus evil.” – I disagree. The hobbits vs. Sauron was definitely good vs. evil.

3) Should I read Miracleman? I’ve never read a page of Miracleman, and until the reboot(?), I didn’t even know there was such a thing. Am I missing something?

3.) I think probably. I read the first couple issues of the re-issued Miracleman when Marvel released them earlier this year, but got bored and fell off. This new series does a) a good job of orienting new readers to the universe and b) kinda seems to take place in a world AFTER the Miracleman family has done all of their big heroics. I am wholly unfamiliar with the franchise, but it’s been absolutely fascinating to read this new series (which isn’t so much a reboot as it is a new, distinct volume). It’s much more welcoming than I usually find Gaiman’s writing to be, and Mark Buckingham is a goddamned rockstar, flexing all his muscles all the time. I will probably campaign to do a full AC on issue 4.