Today, Drew and Patrick are discussing The Fade Out 6, originally released May 20th, 2015.

Fuck you; I gave you a reason to live and you were more than happy to help. You lie to yourself! You don’t want the truth, the truth is a fucking coward. So you make up your own truth.

Teddy, Memento

Drew: The more I think about Memento, the more I love it. It’s easy to see the backwards structure as gimmickry, but I’m absolutely enamored of how it draws us into Leonard Shelby’s subjectivity. And I mean “draws us in” — that the scenes are shown to us in reverse order doesn’t just put us in his shoes, it forces us to trust him in spite of his obvious shortcomings as a narrator. His unreliability is front-and-center from the start, but because we’re lost with him, we have no choice but to trust him. Charlie Parish’s unreliability is decidedly less tangible, but no less central to his story — the whole mystery surrounding Valeria’s death hinges on him not remembering what happened. As The Fade Out ramps into its second arc, his subjectivity becomes an ever more important element of the series.

I’ve always been intrigued at the third-person narration writer Ed Brubaker employs for this series. In our discussion of the first issue, Ryan mentioned that third-person narration was “actually quite common with a specific type of noir popularized in the 1940s: the semidocumentary.” That sub-genre is a hybrid of sorts between noir and historical fiction, where real-world events and characters are woven into a fictional story. In many ways, that’s exactly what The Fade Out is: real-life figures like Desi Arnaz and Dashiell Hammett rub elbows with fictional characters (many of whom are based on one or more real-life figures, as well).

Actually, it’s even more complicated than that, as Gil engages in his own pseudo-semidocumentary — his “murder story,” where third-person is necessarily employed to (poorly) hide his role in the proceedings.

Aside from suggesting that Brubaker maybe knows something about a murder, this scene presents a false semidocumentary. Like a semidocumentary, Gil’s “story” is based on real people and situations, but instead of having fictional components, he’s just pretending that the story is fictional. The fiction itself is fictional — it’s a straight-up true story he’s just calling it fiction to cover his tracks. In a way, I think Gil’s pseudo-semidocumentary is a twisted reflection of the series as a whole.

I must confess I wasn’t familiar with the semidocumentary until Ryan brought it up in that write-up, but my understanding is that they employ third-person narration specifically to imply factual authenticity — that is, an objective perspective removed from the angles of any of the characters within the narrative. This series, however, employs a narrator that is increasingly subjective — never more than at the start of this issue:

This moment in particular stood out to me. The kind of instant back-pedal suggests that this is an account of what Charlie is thinking in real-time — as though this is an account of his own perspective. At the very least, the fact that the narrator corrects himself suggests a much more conversational tone — this isn’t a manicured, edited account of the events.

But what if this is an account of Charlie’s perspective? What if, like Gil, Charlie’s just using the third-person to distance himself from a story he’s actually involved in? I know that seems like a bit of a reach, but this issue is dripping with Charlie’s subjectivity.

This is by no means the first time artist Sean Phillips has projected Charlie’s thoughts on the scene he’s in — that was a key moment in issue 4 — but this is the first time it’s been so explicitly tied to physical media. I’m referring, of course, to the halfdot pattern in the second panel, which suggests that the image is coming from a newspaper or magazine and not from inside Charlie’s head. It’s as though someone is reflecting back on this moment after the fact, perhaps using this photograph as real-world evidence of the story they’re telling

My suspicions about the narrator aside, this issue is incredibly rich. I’m particularly struck by the duality of Charlie and Gil, which Brubaker illustrates by bringing up their theories on alcohol. Id-driven Gil sees the loss of inhibitions as a good thing, releasing his inner self, while ego-driven Charlie feels like those inhibitions are what makes him who he is, and losing them turns him into an idiot. That kind of open statement of who these characters are would feel a bit hackneyed if it wasn’t so well-supported by their actions throughout the series. More importantly, this issue finds both characters turning to alcohol for courage, but they feel decidedly different about their actions afterwards.

Man, Patrick, I barely touched on one-tenth of what I wanted to. In the spirit of letting you make up your own truth, I’m not going to try to prompt you other than to ask if you recognize any of the locations this go-round.

Patrick: Oh sure — definitely recognize Charlie’s little walk under the tracks of the Angel’s Flight, which is this sort of trolley downtown that traverses like four city blocks, but does so at an absurd incline. It’s my understanding that people used to take the Angel’s Flight as a matter of transportation — there’s a pretty rad farmer’s market near the lower station — but now, it’s largely a tourist attraction. Not a well-trafficked one, but a relic of a weird time when people prioritized that space differently.

The rest of the issue is actually pretty well focused in on the characters and interiors, which serves to elevate the fantasy of the “The Ranch” that pops up several times throughout the course of the issue.

The mystery that Charlie thinks he’s working to uncover at the Ranch speaks to Drew’s idea the semidocumentary as well. Charlie runs into Flapjack Jones, one of the former actors from the children’s show “Krazy Kids” and pumps him for information about what went on back in the show’s heyday. Context clues make it clear enough that “Krazy Kids” is essentially “Our Gang” (which would later be repackaged and syndicated under the title “The Little Rascals”). There’s even an article in the back matter written by David Faraci about the racial significance the “Our Gang” shorts had back in 1922 — it’s an insightful piece and I encourage everyone to read it. But it’s not like those racial issues are overtly at play within this issue, so what does that piece effectively do for the story of the issue? Well, it legitimizes the connection between “Krazy Kids” and “Our Gang,” so as Faraci places the real show in its historical context, the reader cannot help but place “Krazy Kids” in the same context. That’s fiction and history intermingling to create something stronger than fiction alone, but possibly more compelling than the truth.

And, oh boy: the truth. I love this idea that the narration has to come from somewhere — it so obviously has a perspective, how could it not also have an origin? The thing is, Brubaker isn’t coy about where writing comes from in this series. One of the main thrusts of The Fade Out is the contentious partnership of Gil and Charlie, working together to write a screenplay. Even if Gil is the muscle and Charlie is the face, their resultant work is a collaboration. Shouldn’t we assume the same is true about the omniscient narration which often appears to take on Charlie’s perspective? Add to that the writers’ insights about what liquor “was good for.” There are roadblocks — editorial stops — in place that prevent the narration from being Charlie’s running internal monologue, but his perspective is absolutely at the heart of the storytelling.

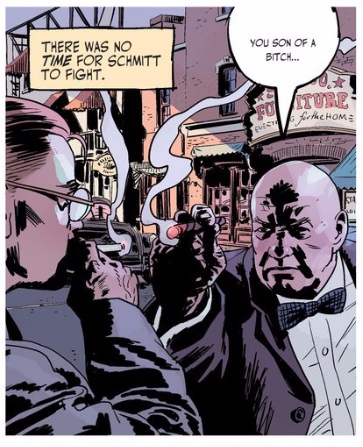

Sean Phillip’s art continues to be astonishingly evocative. I know that narration we won’t shut up about tells his story at a mean clip, but Phillips is no slouch either. Dude tells entire stories, loaded with history, in single panels. Look how clearly he lays out the conflict and power dynamic between Charlie and his director.

Ever the flippant, defiant asshole, Charlie casually takes a drag from that cigarette, but a furious-but-holding-it-all-together Schmitt gestures menacingly with that cigar. The decision to make Schmitt’s lettering extra tiny, without decreasing the size of his speech balloon is also inspired. He’s staying something just as big, but the words are smaller.

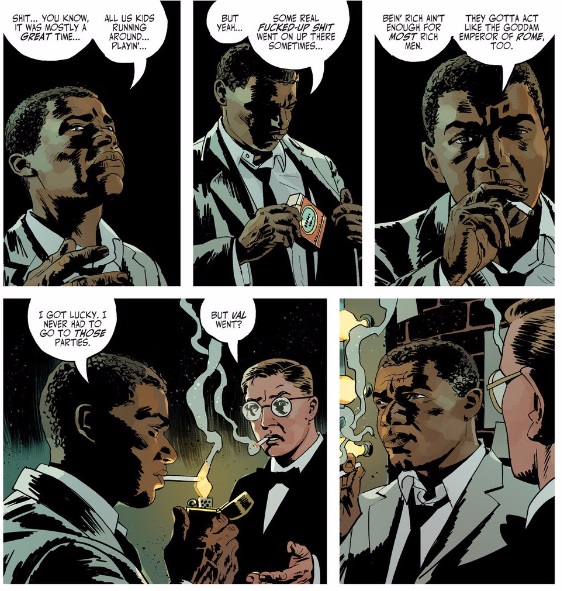

Actually, Phillips gets his most effective acting done between puffs on smoking implements of one kind or another. When Charlie does get back to see Flapjack, the conversation starts to turn to the dark topic of What Happened On The Ranch. Phillips very carefully shows the reader every step in Flapjack’s processing, from retrieving the box of cigarettes from his jacket, to sticking it in his mouth, to lighting it.

It’s a patient walk to that final panel, but the pay-off is amazingly effective. Between the ritual of taking that first drag and the thousand yard stare, we don’t really need words to know that Val was part of something awful at those parties at the Ranch. Y’see, it’s not just about having an unreliable narrator, it’s also about having some parts of the story that refuse to be narrated.

For a complete list of what we’re reading, head on over to our Pull List page. Whenever possible, buy your comics from your local mom and pop comic bookstore. If you want to rock digital copies, head on over to Comixology and download issues there. There’s no need to pirate, right?