Today, Patrick and Drew are discussing The Wake 10 originally released July 30th, 2014.

Today, Patrick and Drew are discussing The Wake 10 originally released July 30th, 2014.

They are our witness. Our memory. Our reflection staring back at us from the surface of the water. Challenging us to be unafraid, to take whatever leap we can.

Dr. Lee Archer, The Wake 10

Patrick: I let a lot of creative projects marinate in my imagination for long time before I ever express them to anyone. As a result, most of these projects never ever ever see the light of day. Half-formed ideas wither and die in my mind on a daily basis — exciting worlds, interesting characters, heartbreak, adventures, mysteries revealed. I know that ever single idea I’ve ever had would benefit from a second imagination’s scrutiny, so why would I let so many concepts suffocate inside my own skull? Because expression is scary. Admitting that you think an idea you have is cool is impossibly risky: literally no one else has ever weighed in on the idea before you. Actually expressing an original story you want to tell (or an original painting you want to paint or an original song you want to sing), requires the artist to be a narcissist and a champion of the unknown at the same time. That’s an incredibly naked position to be in, and that’s how Scott Snyder and Sean Murphy cast the whole of humanity in the final issue of The Wake.

Last month, Drew predicted that this issue was going to be like reading “a goddamn lecture.” That’s 90% correct. The action of the issue is largely contingent on forces we’re not meant to understand, or the motivations of General Marlowe, about whom we also know very little. The will and perseverance of Leeward matters very little in the end, as she amount to little more than a courier, delivering one drop of Original Human Rocket Ship fuel to the ghost/non-ghost of Dr. Archer.

Do we need to recap the chatty revelations in this issue now? Human beings are/were a race of interplanetary colonists that send “seeds” down to habitable planets, allowing nearly-intelligent life to develop before landing on the planet and supplanting the dominant species. The hiccup on Earth was that there were these Mer creatures didn’t much care for that practice. This next step in the mythology didn’t make much sense to me, so bear with me. Here’s the text:

The use of pronouns makes it tricky to say exactly what Lee is talking about. Specifically who the “we” is in this scenario — the humans that descended on Earth or the closest species to human? Additionally, I’m not 100% on what the “it” is that “we” shouldn’t let happen this one time. I guess that’s all immaterial detail, as the overwhelming sentiment behind the story is that the Mers were able to remember this weird proto-life story where the humans were specifically engineered to forget.

The use of pronouns makes it tricky to say exactly what Lee is talking about. Specifically who the “we” is in this scenario — the humans that descended on Earth or the closest species to human? Additionally, I’m not 100% on what the “it” is that “we” shouldn’t let happen this one time. I guess that’s all immaterial detail, as the overwhelming sentiment behind the story is that the Mers were able to remember this weird proto-life story where the humans were specifically engineered to forget.

In true The Wake fashion, the mechanism by which human beings forget is utterly plausible. There’s a chemical in our tears which causes the memory to fade after a generation or two, and that’s the evolutionary advantage that tears present. Snyder delightfully taps our own fascination with the unknown one last time, leveraging the real-life mystery of why human beings cry at all. We really are among the few species on the planet that do. I did some really cursory research here — just enough to notice that typing “why do humans” into Google autocompletes to “why do humans cry?” Filling in the gaps in real science with fiction has been Snyder’s go-to trick throughout this series. Aquatic ape theory, 52 hz whale, mermaids — all real world questions answered by series that tricked us into thinking it was always just posing unanswerable questions.

I suspect that this is going to be one of those ending that comic fans point to as evidence that Snyder doesn’t know how to end stories. The ending is much more satisfying thematically than it is narratively. What I see in the resolution here is that human beings are capable of great, world-conquering, mind-blowing feats, but are incapable as acting as witnesses to their own actions. They need some vicious monsters to see the value in what they’re doing. Humanity here represents artists, and specifically Snyder and Murphy, while the savage Mers represent fans. By allowing us to see the fantastic world they’ve created, populated with tons of far-fetched theories and crazy concepts, Snyder and Murphy are exposing themselves to one hell of a judgmental creature. I mean, just the knuckleheads here at Retcon Punch of written over 10,000 words about this series over that year. And even when we’re excited about one concept, or cooing Murphy’s moody art, we’re still going to bitch about something.

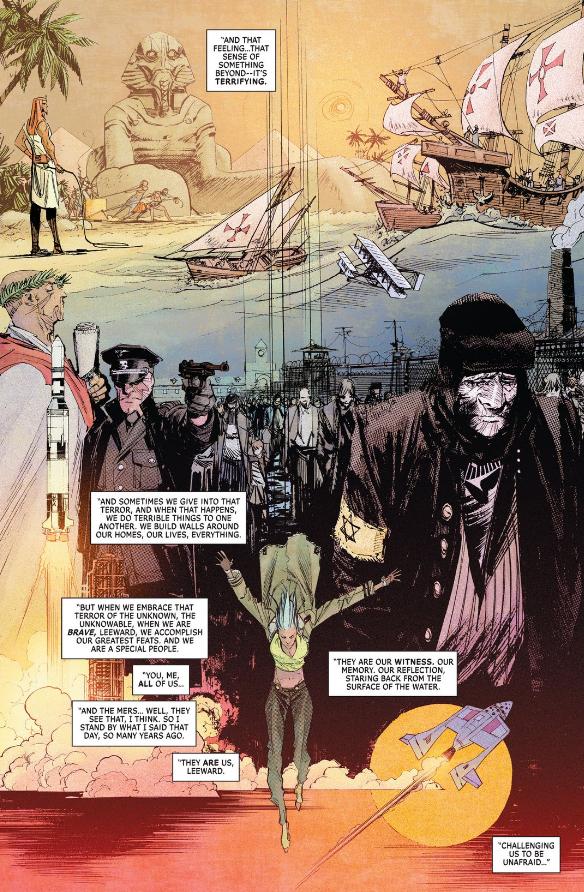

Hey, speaking of cooing: I love that Murphy gets one more shot at the historical-splash-montage that’s been his calling card throughout this series.

This is the loosest copy Snyder’s ever given Murphy for one of these. He’s basically asking him to show the best and worst of humanity at once. It’s a wonderfully evocative image that expresses so many thoughts themes and ideas all at once. This is the kind of urcreation that you and I are made to bear witness to, to tear it down or build it up, but always to remember it.

This is the loosest copy Snyder’s ever given Murphy for one of these. He’s basically asking him to show the best and worst of humanity at once. It’s a wonderfully evocative image that expresses so many thoughts themes and ideas all at once. This is the kind of urcreation that you and I are made to bear witness to, to tear it down or build it up, but always to remember it.

Drew, I have a feeling that that idea resonates with you, but I also know that we are creatures of narrative comforts, and the conclusion to Leeward’s adventure skews most kinds of accepted resolution. Is that an artistic statement in and of itself? Does Snyder want us to be witness to his anti-ending?

![]() Drew: I actually think the artistic statement is a bit bolder than what you suggest. Indeed, I think Lee’s assertion that the Mers are humans is best understood under your reading where humanity “represents artists…while the savage Mers represent fans”. In that way, Snyder isn’t just asserting our role as witnesses of this ending, but as creators of this ending. This issue (and ultimately, this series) reads as a love letter to fans as those who remember — as those who take creators to task when something shouldn’t be forgotten. As a site that occasionally takes creators to task when something shouldn’t be forgotten, that message obviously means a lot to us, but I’m much more impressed that these two comics rockstars were able to come together to assure us that their contributions are at best equal to the readers that ultimately interpret their work. That’s basically the exact same philosophy that led to the creation of this site, so this issue feels as if it was crafted just for us.

Drew: I actually think the artistic statement is a bit bolder than what you suggest. Indeed, I think Lee’s assertion that the Mers are humans is best understood under your reading where humanity “represents artists…while the savage Mers represent fans”. In that way, Snyder isn’t just asserting our role as witnesses of this ending, but as creators of this ending. This issue (and ultimately, this series) reads as a love letter to fans as those who remember — as those who take creators to task when something shouldn’t be forgotten. As a site that occasionally takes creators to task when something shouldn’t be forgotten, that message obviously means a lot to us, but I’m much more impressed that these two comics rockstars were able to come together to assure us that their contributions are at best equal to the readers that ultimately interpret their work. That’s basically the exact same philosophy that led to the creation of this site, so this issue feels as if it was crafted just for us.

As much as I love the meta-text, the twist is only partially satisfying to me. I think the notion that we cry in order to forget is both beautiful and sad. It would certainly protect us from the memory of pain, but it would also mean that our pain no longer informs who we are. Rather than desperately trying to remember deceased loved ones or long lost friends and lovers, we’d simply forget about them entirely. It’s understandable how that state of affairs would prompt such a desperate push to remember that slowly played out through history.

Where I’m less satisfied is in the explanation for how this explains the Mers motivations. They personally brought all of our most intrepid voyagers to this space ship with the apparent goal of helping them leave, but there’s no hint as to why they would do this. Or why they couldn’t have offered to help track down that fuel during any of the last 200 years. Or why they would flood the continents and kill countless humans during that time. It’s cool that they’re good guys, but this explanation doesn’t come close to absolving them of all of those puffs of blood they turned people into during the first half of this series.

Intriguingly, Murphy may give us a partial explanation with his choices in that final montage sequence (the last image Patrick included), which features some familiar high points in human history as well as two notable low points: the Holocaust and slavery. Both are subjects that are painful to remember, but does that represent an upside or a downside to a long memory? Sure, it can be hard to remember the horrors humanity is capable of, but as Santayana suggested, “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Knowing our history allows us to avoid the pitfalls, more than justifying the pain of memory if it allows us to avert another genocide. Apparently, humanity was designed to forget those things, and thus condemned to repeat them, until the Mers came along. In that light, it’s understandable that they would cause pain and growth in equal measure, I’m just not sure killing a bunch of people is the best pedagogical method for helping us not kill a bunch of people.

Patrick called this an “anti-ending,” and I think I may agree with that almost too specifically: in many ways, the resolution here feels like the beginning of two very interesting stories. That makes for a propulsive sense that the adventure continues off the page, but it also means that the resolution doesn’t bring much closure to either Lee or Leeward. I suppose they both get to continue exploring, but Lee has to do it without her son, and Leeward has to do it without anyone (you know, besides Dash). Maybe this is more meta-text, giving the audience the power to decide what happens next — a kind of less explicit “The Lady or the Tiger?” — which makes for an empowered audience, but isn’t the most emotionally satisfying ending. Which do we value more? In the spirit of audience participation, I’ll leave that question to the comments.

![]() For a complete list of what we’re reading, head on over to our Pull List page. Whenever possible, buy your comics from your local mom and pop comic bookstore. If you want to rock digital copies, head on over to Comixology and download issues there. There’s no need to pirate, right?

For a complete list of what we’re reading, head on over to our Pull List page. Whenever possible, buy your comics from your local mom and pop comic bookstore. If you want to rock digital copies, head on over to Comixology and download issues there. There’s no need to pirate, right?

I don’t think the second half of The Wake ever worked for me like the first did. That horror movie vibe in the first half was just so elemental, while the tone of the second never really jibed for me. That said, as offbeat as it is, I kind of like this ending. From a pure narrative sense I can see why it’s a bit frustrating, and I don’t know if everything really adds up, but it’s such an interesting, deep, novel idea that I can’t help but to be charmed by it anyway.

Her mind is full of bubbles, she got the decompression bends

She got a lot of ancient mermaid monsters she calls friends

How they cry in the ocean, sad, cold and wet.

Some cry to remember, some cry to forget.

Her mind is Tiffany-twisted, she got the Mercedes bends

She got a lot of pretty, pretty boys she calls friends

How they dance in the courtyard, sweet summer sweat.

Some dance to remember, some dance to forget

In the end… worth buying the graphic novel?

That’s an interesting question. I think: yes, definitely. But it’s important to go in with the expectation that you’re going to be thematically satisfied, if not necessary narratively satisfied.

Also, the whole thing could be a narrative and thematic shitshow and Murphy’s art would make it worth the purchase alone. I intend to pick up a copy when the trade comes out – there’s no one that really does what he does, and I’d love to have that on my shelf.